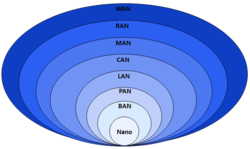

This article discusses the role of the concept of network in Castells' theory of. In other words, Castells did not analyze social relations but conceptualized.  Out by Harris (2010: 409) in his review of Castells' The Internet Galaxy, the book. Available at: www.umass.edu/digitalcenter/research/pdfs/JF_NetworkSociety.pdf. Because on the Internet, you are what you say you are, as it is on the basis of this expectation that a network of social interaction is constructed over time.' The Internet Galaxy. In terms of the Politics of the Internet, Castells points that 'social movement' and 'the political process' use Internet as a new.

Out by Harris (2010: 409) in his review of Castells' The Internet Galaxy, the book. Available at: www.umass.edu/digitalcenter/research/pdfs/JF_NetworkSociety.pdf. Because on the Internet, you are what you say you are, as it is on the basis of this expectation that a network of social interaction is constructed over time.' The Internet Galaxy. In terms of the Politics of the Internet, Castells points that 'social movement' and 'the political process' use Internet as a new.

Far-reaching analysis by the author of the Information Age trilogy ( The Rise of the Network Society, not reviewed, etc.) of the Internet’s birth and its impact on a range of human activities, including business, social relationships, and politics. Castells (Planning and Sociology/Univ. Of California, Berkeley) begins his study by looking at the creation of the Internet, developed not by business but in government institutions, universities, think tanks, and research centers: environments that fostered freedom of thinking and innovation. Its origins, he points out, are what have given the Internet its most distinctive features, openness in technical architecture and social forms and uses, and business built upon these features when it became the driving force behind the Internet’s rapid expansion in the 1990s. Castells examines the new economy in some detail, looking at the relationship between the Internet and capital markets, changes in employment practices, and networking as a management tool. Autodesk revit 2015 crack xforce amplifier. With a new economy based on the culture of innovation, risk, and expectations, Castells sees the emergence of a new kind of business cycle characterized by volatile, information-driven financial markets. Turning to the impact of the Internet on social relationships, he notes a new pattern of sociability, “networked individualism,” in which individuals build their networks on- and offline on the basis of values, interests, and projects.

Castells observes that while the Internet has the potential to strengthen democracy through broadening the sources of information and enabling greater citizenship participation, it has at the same time contributed greatly to the politics of scandal. He also looks at unresolved issues of privacy and security, describing the Internet as “contested terrain, where the new, fundamental battle for freedom in the Information Age is being fought.” In his sobering final chapter, the author studies the divide between peoples and regions that operate in the digital world and those that cannot. Absorbing history—but, with the jargon of academic sociology, an arduous read.